As discussed on my News page, I was recently involved with the British Film Institute release of a DVD and Blu-Ray of the work of my mentor Dr. Don Levy.

I encourage everyone with a Blu-Ray player to buy the all-region disc. The DVD is also region-free, but it’s PAL so you need to be able to deal with that.

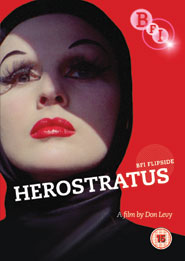

The finished copies arrived in my hands yesterday and I have to say the BFI did a really nice job! From the striking and perfectly emblematic cover (featuring Don’s widow, the remarkable Ines Levy who collaborated with him in a variety of ways, including appearing in all his films and playing a number of visually striking roles in Herostratus), to the booklet which not only covers all of the films on the disc but offers a touching piece about Herostratus‘ lead, Michael Gothard (never mind the small number of really good films he did, like Ken Russell’s The Devils; try watching a piece of crap like Scream and Scream Again and see how the film comes to life when Gothard appears). There’s also a fascinating piece by Henry K. Miller about the Slade School of Art, where Thorold Dickinson started the first University film program in the UK, and Levy (fresh from a PhD in Chemical Physics at Cambridge) was one of his first two students — the other being Ray Durgnat.

It’s been a long road. When I first approached the BFI in 2006 about a DVD of Levy’s Herostratus (1967), no one was the least bit interested in doing anything with this important piece of their own history (the first feature film the BFI financed). Eventually there was a shakeup in the content department there, and Jane Giles (Head of Content) and Sam Dunn (Head of Video Publishing) arrived. As anyone who loves cinema and is a DVD addict like me knows, the BFI has quickly become one of the most adventurous and creative labels around. They put Herostratus into their plans almost immediately, and, along with the disc producer Shona Barrett, have done a great deal to see that it’s done right.

(I won’t get into a misty-eyed gush here about how amazing it is to this old cinephile, to be living in days when a film like Herostratus, a film maudit if ever there was one, can get this kind of treatment. At Cal Arts, in the late 70’s/early 80’s, I programmed the public film series. I had a substantial budget to rent 16mm and 35mm prints — about three films a week — only most films that I wanted to show had no more extant prints. And when there were prints, your $50 rental got you 4000 feet of mercilessly banged-up celluloid.)

Even those who have a hard time with the aggressive and extreme Herostratus are beguiled by Levy’s short films, and I’m especially happy that the BFI was able to include several of the most important ones. They are little jewels that still dazzle.

In case it helps convince you that you need this for your library, or in case you want to read my essay without buying the disc, here it is:

***

Amidst the digital renaissance yielding up the fruits of the first century of cinema, “here is something completely new.” Until now, Don Levy’s 1967 Herostratus has existed only in a handful of 35mm prints, long ago faded to monochromatic magenta. Moreover, in spite of the bright flare of excitement the film generated among filmmakers and festival programmers upon its original exhibitions, its historical stature has faded as surely as the colour dyes in its emulsion.

Remarkably, the present release is the film’s first commercial distribution in any format. Given its concern with the psychic forces that manifest as history, perhaps Herostratus can only be properly seen through generational distance. The mistake then would be to see it merely as an artifact. If it is a kind of time capsule, it is one of enormous aesthetic refinement; its obscurity is a measure of its scientifically calculated transgressive force. Less time capsule perhaps than trauma capsule.

Shooting on Herostratus commenced on August 20, 1964 and took place over the following 8 months. The great wave of post-war cinema was at its artistic peak on the continent, but UK filmmaking had yet to take the same kinds of bold artistic directions.

Indeed: both narratively and formally the film depicts the meeting of shabby and dreamless post-war Britain (embodied in the desolate apartment that Max demolishes in the early scenes) and the generation that seemed to arrive at the very moment the film was being made. In the same manner it marks out the transition from the serious British filmmaking that preceded it (earnest kitchen sink realism) and that which followed (psychedelic dislocation a la Petulia, Performance, etc.). Described during its making by one publication as “the great white hope of British art cinema,” pillaged for ideas by several films shot after it but released before it – not to mention many others made subsequently — seen by virtually every filmmaker then working in the British film industry when it was the opening exhibition at London’s ICA cinema in May 1968, Herostratus must now certainly rank among the most influential of unknown films.

In addition to the Europeans, (most apparently, Antonioni) Herostratus owes a debt to the works of American experimental filmmakers such as Brakhage, and Markopolous. But whereas their films were deeply, explicitly personal in frame of reference, Levy goes in the opposite direction. He laces his film with documentary material to claim an objective framework. Herostratus is not a confession, but neither is it an accusation. It is, or wants to be, a revelation.

Levy seeks to expose the neurosis that is exploited and sustained by social institutions. His intent is not to offer critique but simply to reveal the viewer’s wounds – the fear of death, longing for love, unfulfilled desire for meaning – the unconscious forces that are manipulated by advertisers, employers, entertainers, warmakers.

The film’s method is to traumatize its audience, and then to cauterize the wound with beauty. It is a uniquely gentle trauma, avoiding the safe horror of the Other, holding up instead a mirror. It wants to traumatize us not for the sake of sensation, but as a diagnosis.

Clearly this is a film by, as well as about, an angry young man. It is a young man’s film in both its urgent desire to hold the world to account for its wrongs, and in its own virtuosic ambitions.

Yet, with a precision even an Antonioni or a Godard was unable to muster, the film prophecies the inevitable failure of the 60’s youth rebellion – at a moment when it had scarcely even begun: that it would be defeated ultimately not by an adversarial power structure, but by its own human weakness, its egotism and narcissism.

Herostratus dramatizes our condition as one of entrapment, implying that its own purpose, the purpose of art, is to make the trap known. “You can get out,” a voice (the filmmaker’s) shouts at the character Clio, named for the muse of history. Herostratus is a cry for catharsis, a need it proclaims, through negation, both narratively and formally.

Rejecting the linear structure of a traditional narrative, or the non-linear structures already being explored by European filmmakers, Levy employs cyclical patterns of structure more typical of non-western music. The overall design is that of a cycle: the end and beginning are fused, and the film’s time-progression is not primarily the unfolding of a plot line but the descent into deepening layers of meaning through the repetition and variation of visual and sonic imagery.

Where linear structures maintain their form through the tension between beginning and end, cyclical structures are defined by the tension between pre-existing opposites they encompass, and the way that tension is transformed while the opposites essentially remain.

The opposites deployed in Herostratus, both aesthetic and thematic, are extreme. Warm colours carefully opposed to cool colours; bright slashes of light against frequent bursts of darkness; dialogue scenes drawn out to the rhythm of real life, sometimes painfully so, contrasted with non-narrative visual strands that erupt in durations under a second; all dialogue recorded live yet integrated into a frequently surreal soundscape (involving the same kind of network of cross-associations as the visuals); passages of utter silence against ferocious explosions of music and sound; documentary (newsreel) material interspersed with the most highly composed staging.

The film’s thematic concerns are equally polarized. Consider a sequence that occurs 77 minutes in. An unforgettable two minutes, in which a striptease is intercut with the slaughtering of a cow, provide a nodal point for two strands of images that (along with a half-dozen others) recur throughout the film, subterranean psychic currents periodically erupting into visibility.

One of the remarkable things about this sequence even on first viewing is the sheer aestheticism of even the carnage, which is just as carefully lit and framed as the stripping. This is crucial to Levy’s aim, which is to present not a document of an animal being slaughtered, depicting a stage in the industrial food process, as in virtually all other photographic slaughterhouse records (Franju’s Le Sang des Bêtes being the magnificent paradigm). Levy is rather portraying something going on in the psyche, and the point is in the juxtaposition. The rending of flesh and the revealing of flesh, the inner contents of a dying body spilling out repulsively, the naked living form teasingly disrobed. Death and sex. Deathsex.

The intent is not symbolic. The subject of the sequence is the attraction and revulsion it inspires, the mixture of beauty and horror; not the idea of the fusion of Eros and Thanatos, but the experience.

Outside of this 2 minute sequence, the slaughter imagery recurs only eight times in the film, on five of those occasions being less than a second in length, and none of the other three more than five seconds. Images of the stripper are used as intercuts at five points outside of the main sequence. Even having seen the film multiple times, it comes as a surprise how minimal is the screen time actually occupied by these images (and how precise the intent of each repetition). Levy spent over two years editing the film, and the results testify to a scientific interest in the psychological effect of shot duration and repetition, among other elements of cinematic form.

Don Levy was in fact the rare hybrid of artist-scientist. After completing his PhD at Cambridge in Theoretical Physics, his most important short films were made as part of the Ancestry of Science series for the Nuffield Foundation for the History of Ideas. (Notably Time Is, included in this release, which reflexively reinvents what an educational film can be.) But all of Levy’s work – the majority of which, from the 1970’s and early 1980’s, remains unreleased – reflected both an extremely refined artistic sensibility (he was an exhibited surrealist painter) and a scientist’s interrogation of the medium: its complex physical and chemical dimension, its involvement with light and time, its engagement with the membranes of our senses.

Unlike most artists who have been concerned with these material and perceptual properties of film, Levy was also deeply interested in human behavior. His approach to the performances in Herostratus, and their narrative framework, owes little to either conventional film storytelling, or the minimalist posing then prevalent in European art cinema. The film’s dramatic scenes occasionally have the awkwardly protracted feel of acting workshop improvisations. Yet something very calculated is going on. Levy is seeking to induce a psychological state in the audience through the witnessing in his actors of a deeper emotional reality than we are accustomed to. Levy’s actors are surrogates for his audience, undergoing a traumatic initiation. The goal, which one senses is both personal and artistic: to find what it takes to escape the trap. Ultimately, neither Levy, nor his heartbreakingly gifted lead actor Michael Gothard succeeded. Levy took his own life in 1987, Gothard in 1992.

Nevertheless, the film remains: an act of faith in its audience. That we are willing to relearn how to watch a movie; that we will accept severe psychic disturbance and then examine our own response. This is a faith which distributors were unable to share. There was a feeling that if only Levy would cut the film down to a more “reasonable” length, it might be possible to sell the thing.

But Herostratus was determined to be indigestible to the system. As such its negative, unearthed in pristine condition for this digital restoration, may represent the last true relic of an era that has been thoroughly absorbed by the institutions it portended to attack. If the counter-culture proved simply to be the R&D wing of the corporate mainstream, Herostratus carried a genuine poison pill.

The charge most commonly leveled against the film by its detractors is “pretentious.” The film’s ambitions are grandiose, it is true, and Levy occasionally overreaches; the inclusion of (a tiny number of) Holocaust and Hiroshima images, while carefully considered in terms of the film’s argument, overloads its artistic syntax. The use of footage of Allen Ginsberg from Peter Whitehead’s Wholly Communion now appears a misjudgment, encouraging a misreading of the film’s precise dialectics as 60’s folderol.

Yet no work that embodies such artistic and technical rigour merits such a dismissal. Has there ever been a film this marginal in terms of its budget and production resources that displayed such commanding visual control? Herostratus was made with a budget of approx. £10,000, its unpaid cast and crew taking public transit to reach shooting locations. Viewing the film in the digital realm offers an opportunity to study the astonishing rigour of Levy’s compositions and montage. For example, review the opening sequence of Max running through the streets. Note not only the architectural purity of the compositions and the remarkably delicate use of colour, but, within and between each of the dynamically mobile shots, the precisely contrived interplay of light and shadow. Such careful analysis begins to reveal the extent of Levy’s use of subliminal forces to affect the viewer.

The astonishing collaboration between Levy and his cinematographer Keith Allams is all the more remarkable for the fact that neither man ever made another feature film. Yet if the film’s visual and editorial virtuosity suggest a young filmmaker saying, “hey, see what I can do!” the images and the montage are always connected to its themes at the deepest level. Consider how, in a single, stunning, 360-degree pan, the camera evokes for us the reality of a lost life, a person gone from the world.

If the film’s method and artistic intent was generally rejected in its native land (and little seen outside it) its stylistic innovations were absorbed by a generation of British filmmakers every bit as much as by Levy’s students when he went to teach (from 1970) at the California Institute of the Arts. Herostratus has always cast its spell primarily on filmmakers. Until now it has been a well-kept secret; the BFI’s release of this digital restoration reveals one of the truly underground works of the cinema.